If a local government allows homes to be built in high risk communities and doesn’t build or manage infrastructure in a way that mitigates that risk, could it be as responsible for disasters as an electric company that similarly installs and operates electric lines to serve those areas? That question was handed to a Los Angeles County superior court judge on Friday by Southern California Edison.

SCE’s wildfire liability problem isn’t as apocalyptic as Pacific Gas and Electric’s, but by any other measure it’s bad. The damage from 2017 and 2018 wildfires linked to SCE’s equipment is well into the billions of dollars range. That’s because utility companies – electric or telecoms – that take advantage of the right of way privileges granted by California law are responsible for paying the full cost of any damage that results – by “inverse condemnation” – even if they’re only partly to blame.

As are government agencies, that likewise use private property for public purposes.

With that in mind, SCE filed a complaint against Santa Barbara County, a couple of local special districts and Caltrans. They are accused of improperly allowing homes to be built in a disaster prone area, and otherwise mismanaging flood control responsibilities, road and bridge design and emergency evacuations.

The specific issues in the case involve the deadly and destructive mudslides in Montecito in 2017, that followed the massive Thomas fire that, in turn, was allegedly caused by SCE’s equipment. But if courts eventually accept SCE’s logic, then cities and counties could also be held responsible for wildfire damage if they make poor decisions about where homes may be built. According to SCE’s filing…

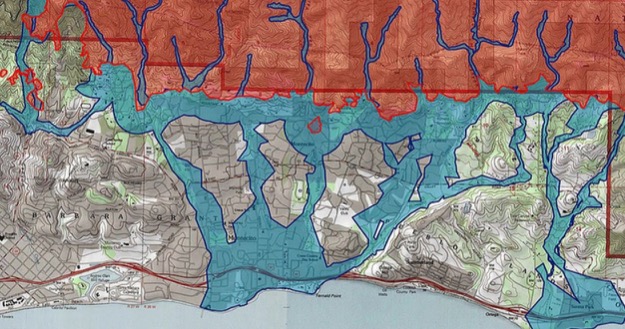

Santa Barbara County was…obligated to appropriately restrict development and redevelopment in unincorporated areas, including Montecito, where improper developments could risk diverting and exacerbating floods and debris flows and would face increased risk of themselves succumbing to natural disasters. However, the County failed to comply with its own obligations or adequately enforce its own ordinances, as Montecito continued to develop quickly. By 2018, the open agricultural areas that once dotted Montecito had largely disappeared, replaced by densely packed residences, commercial buildings, bridges, roads, and other structures that encroached upon the natural floodplain and floodway, often in violation of the County’s Floodplain Ordinance…

The development and associated infrastructure constructed or permitted by the County in these areas created obstructions that exacerbated damages from debris flow events and placed area residents in harm’s way…

Where, as here, the public entity “has made the deliberate calculated decision to proceed with a course of conduct, in spite of a known risk,” just compensation is owed.

SCE is pushing back in other ways against the inverse condemnation principle, and the strict liability that results. It’s asking the California supreme court to limit the way the principle is applied and, along with PG&E, jumping in on a similar case brought by San Diego Gas and Electric. Lower courts have not been sympathetic to SCE’s arguments, but the magnitude of the problem and the diversity of possible contributing causes – climate change, demographics and land use policy, for example – could convince the California supreme court to consider whether current practice does sufficiently “socialise the burden” of wildfires, as California law presumes.