Aaron’s Law wouldn’t have kept Aaron out of prison.

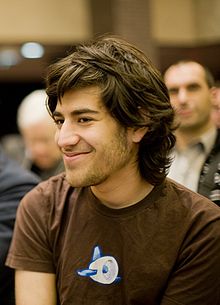

A Silicon Valley congresswoman and an Oregon senator, both democrats, are introducing parallel bills that would tighten up the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (CFAA). Zoe Lofgren and Ron Wyden are titling it Aaron’s Law, in honor of Aaron Swartz, an Internet activist who committed suicide after being charged with a tall stack of felonies for downloading a library’s worth of pay-walled academic journal articles at MIT. Federal prosecutors motivated by ambition and not justice were threatening him with 35 years in prison.

Lofren and Wyden laid out their case for taking civil disputes over terms of service out of the reach of criminal law in a Wired editorial…

Vagueness is the core flaw of the CFAA. As written, the CFAA makes it a federal crime to access a computer without authorization or in a way that exceeds authorization. Confused by that? You’re not alone. Congress never clearly described what this really means. As a result, prosecutors can take the view that a person who violates a website’s terms of service or employer agreement should face jail time.

So lying about one’s age on Facebook, or checking personal email on a work computer, could violate this felony statute.

CFAA was written and passed in 1986, so it’s no surprise that it lacks a level of nuance and specificity appropriate to the Internet age. Aaron’s Law would restrict prosecutions to genuine cracking…

Access without authorization means (A) to obtain information on a protected computer; (B) that the accesser lacks authorization to obtain; and (C) by knowingly circumventing one or more technological or physical measures that are designed to exclude or prevent unauthorized individuals from obtaining that information.

Ironically (or maybe cynically – Washington is what it is) what Swartz allegedly did would still be a crime. He was said to have connected a laptop to a server inside a locked closet, which may be fairly characterised as circumventing technological and/or physical security measures. But it would prevent aggressive prosecutors from piling on dozens of years in prison for what would otherwise be a straightforward burglary charge.

So far, Wyden is carrying the bill alone in the senate, but Lofgren has lined up a bipartisan slate of co-authors in the house.