Another proposal for project funding from the California Advanced Services Fund (CASF) surfaced over the weekend. Race Telecommunications is proposing to offer fiber-to-the-premises (FTTP) service to homes and businesses in the high desert towns of Mojave and Boron, and some surrounding areas.

Another proposal for project funding from the California Advanced Services Fund (CASF) surfaced over the weekend. Race Telecommunications is proposing to offer fiber-to-the-premises (FTTP) service to homes and businesses in the high desert towns of Mojave and Boron, and some surrounding areas.

They’re asking CASF for $6,229,864 for the Mojave segment of the project and $6,780,528 for the Boron piece. The segments are really two halves of the same project, but CASF procedures require separate applications for segments that are not in contiguous areas.

Race is claiming that the areas named in the applications qualify as unserved, which would make them eligible for up to 70% grant funding. The total grant request is $13 million, so if you assume they’re asking for the maximum percentage, they’d have to contribute something like $5.6 million, for a total project cost of, say, $18.6 million.

This proposal will be very interesting to watch as it makes its way through the CASF review process. In order qualify the project for unserved area funding, Race will have to challenge the data that the California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC) has on its current broadband availability map and in its recently completed Spring 2012 mobile broadband field testing trial.

This proposal will be very interesting to watch as it makes its way through the CASF review process. In order qualify the project for unserved area funding, Race will have to challenge the data that the California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC) has on its current broadband availability map and in its recently completed Spring 2012 mobile broadband field testing trial.

The entire area is covered by mobile data providers, including AT&T, Verizon, Sprint and, in Mojave, T-Mobile. Or so the providers say. The level of service they claim to offer does not reach the 6 Mbps up/1.5 Mbps down standard adopted earlier this year by the CPUC, but it’s enough to get an “underserved” rating. Underserved areas are only eligible for up to 60% funding, and applications for projects in those areas can’t be submitted until February 2013. So Race has an incentive to make an early case for “unserved” funding.

The CPUC’s Spring 2012 field trial had several test points in Race’s project area. The test data back up the providers’ claims, to a certain extent, and support the underserved designation, at least for broadband service accessed outdoors on a smart phone or laptop computer. One way Race might challenge the mobile broadband availability data is to show that it can’t be accessed to a sufficient standard by people using it inside their homes.

Wireline broadband service is available at speeds that also qualify as underserved from Charter Cable and AT&T in Mojave, and from Charter and Verizon in a small pocket west of Boron, at least according to the data they provided to the CPUC’s mapping project. This data is supported, somewhat, by information that Race provided in 2009 and 2010 when they applied for broadband stimulus grants. This proposal is actually the fourth that Race has submitted for a fiber project in this sparsely populated stretch of eastern Kern County.

If wireline DSL and/or cable modem service is actually available to some homes and businesses, then it will be much harder for Race to challenge the current underserved designation in those areas. The CPUC’s challenge procedure would require them to either provide evidence that residents cannot order any DSL or cable modem service now, or take on the much more difficult task of showing that the service available is so bad that it is effectively only as good as dial-up service. The CPUC hasn’t precisely defined what that benchmark means, but the lowest download speed they specify for inclusion in their availability map is 200 Kbps. If an applicant can show that the available DSL service doesn’t meet that low mark, it might be possible to convince the CPUC that the area really is unserved. Might be possible.

Or might not be. In that case, CPUC staff could trim out the areas they consider to be underserved (Race should be able to reapply for those in February), and fund the rest, in the process presumably reducing the grant amount on a pro-rata basis. Or, they might reckon it to be a hybrid project – one that includes both under and unserved areas – and tell Race to refile the whole thing in February, still with 70% funding for the unserved areas but only 60% for the ones CPUC deems to be underserved.

Of course, the CPUC process is open to all. Incumbent providers can challenge Race’s claims and the CPUC’s own data, and try to prove that the project area is not eligible for CASF subsidies. Once a draft resolution has been released, any interested party can comment, for or against. It’ll be up to CPUC staff and, ultimately, the commissioners, to validate or reject the unserved designation for some or all of Race’s project area.

The February funding window is likely to be more crowded. Right now, it looks like only three projects comprising five applications (the others are in Mendocino and Monterey Counties) made last week’s unserved deadline. Since underserved areas tend to be more densely populated than unserved areas, it’s generally easier to make a business case, even with the lower grant funding level.

The information just released about this latest application does not give much technical or financial detail on the project. Race is calling it a last mile, FTTP network that will serve 100% of the homes in the areas in Mojave and Boron that they’ve defined in their application. They say that “speeds will start at 15Mbps down and 10Mbps up.” Pricing information was not included in this summary.

Mojave and Boron are small towns with something like 1,300 homes each, if you include some of outlying desert areas. The implied cost per household passed is in the neighborhood of $5,000 for the CASF grant. Race’s implied out-of-pocket cost per household passed would consequently be somewhere around the $2,000 range.

If they can achieve a 50% take rate (to pick a number arbitrarily), the book value of a subscriber would be something like $4,000. That’s on the higher end of the normal range of per sub valuations, but if they can get television, telephone and other revenue from subscribers, it’s not impossible to make a business case.

The area is situated on the main road trip route between central California and Las Vegas. Edwards Air Force Base is just to the east of Mojave and south of Boron. As the first commercially licensed spaceport in the U.S., Mojave Air and Space Port is a hub of private aerospace development. It hosts a number of entrepreneurial high technology ventures, including the development and testing of Space Ship One, the first private spacecraft to carry a man into outer space.

Boron’s history is more prosaic, if no less fondly remembered. It’s the site of the world’s largest borax mine and the spiritual home of Death Valley Days, a mid-Sixties television series sponsored by 20 Mule Team Borax and hosted by Ronald Reagan.

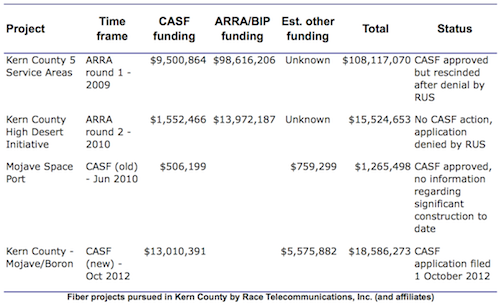

There is a wealth of information about Race’s three previous broadband grant proposals. They made two applications to the broadband stimulus programs funded by the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) in 2009 and 2010. Both times, they applied for matching funds from CASF. In the first round, they went large, asking for nearly $100 million in grants and loans from ARRA and $9.5 million from CASF. The CASF money was approved contingent on ARRA funding, which was eventually denied. Brighthouse Networks challenged some of Race’s claims, but there’s no evidence they swayed the decision.

Race scaled back and put in two more proposals. One was of a similar scope to this latest one, asking ARRA for about $14 million and putting in another request to CASF for 10% matching funds. Altogether, the project was worth about $15.5 million, according to their ARRA application.

Race also applied for a smaller CASF grant of about $500 thousand to build a fiber network at the Mojave Air and Space Port. According to the CPUC resolution that approved the grant, CASF was paying for 40% of the cost (the maximum under the old program), with Race contributing the 60% balance of about $760 thousand, for a total of $1.3 million.

The second round ARRA proposal was also denied, but the smaller CASF-only project moved forward. According to the CPUC resolution,

Race will establish a regional central office and co-location facility, and build a regional optic backbone network to serve one market within Kern County. One local distribution ring will be built from the data center and central office to serve the businesses in the designated markets of Mojave.

The total proposed project of 5.1 square miles surrounds unserved and underserved areas of 231 businesses. Race proposes to reserve some portions of its internet capacity for public benefit organizations such as fire and police departments, hospitals, and educational institutions which desire to have their own fiber optic network to improve community services. Race estimates that the project would be completed within 24 months from the beginning of construction.

According to data provided in May 2012 by the California Emerging Technology Fund, the Mojave Space Port project was 10% completed, with only design and engineering work done. That information is consistent with postings on Parabolic Arc, a local blog, that referenced delays in getting right of way approvals. As of September 2012, the project was not yet in operation.

The Race website has information about the network architecture and vendors who would have supported the ARRA-funded proposals, had one been approved. The company planned to build a central office in Mojave and link it to the One Wilshire data center in Los Angeles, an element that was also included in the Space Port project. From this central office, they would serve local hubs in Mojave, Boron and, originally, three other Kern County towns (California City, Rosamond, and Tehachapi/Arvin). These hubs would then feed a GPON fiber network deployed to all homes and businesses in their service area. Vendors included Calix, Infinera, Force 10 and TwTelecom. Customer premise equipment was said to be Gigabit capable.

Pricing ranged from $15 per month for 1 Mbps up/down for residential customers all the way to $200 per month for 100 Mbps down/25 Mbps up to businesses, according to their website. Mid-level residential service of 25 Mbps down/15 Mbps up would have cost $45 per month and, according to the CPUC resolution, a similar package that was – presumably still is – to be offered to businesses at the Mojave Air and Space Port was priced at $60. These figures might be a guide to their pricing strategy for their latest proposal, which begins at 15 Mbps down/10 Mbps up.

A $13 million grant for two small California desert towns, subsidizing 70% of say, a $7,000 cost per household is high. A comparable FTTP build in urban or suburban areas of the state might be half that, or less. It represents close to 10% of the money remaining in the CASF infrastructure kitty. On the other hand, the reason CASF exists is to build broadband infrastructure in areas that are too expensive for private capital to fully fund. The Race Telecommunications proposal is a good opportunity for the CPUC to define what that mission statement means.

Downloads:

2012 CASF application summary submitted by Race Telecommunications, including maps

2011 CPUC brief on Mojave Air and Space Port project

2010 CPUC resolution authorizing Mojave Air and Space Port grant

2010 summary of second ARRA grant proposal submitted by Race

2009 CPUC resolution authorizing matching grant for Race’s first ARRA proposal

2009 executive summary of Race’s first ARRA proposal